Cancel Isp and Start Again for Discount

If there'south one caption for the dysfunctional land of home internet service in the U.Southward., it's a lack of competition. With simply i or ii options for high-speed broadband in most places–or no options in rural areas–consumers have little ability to escape routine cost hikes, data caps, overage charges, the erosion of net neutrality, and weak privacy protections.

That'southward why the birth of wireless home internet has been so frustrating to detect. While major telcos similar Verizon and T-Mobile make grand proclamations nearly disrupting dwelling broadband with speedy 5G wireless internet service, the reality on the ground–or, rather, in the air–is harsher. Even with low buildout costs and limitless consumer demand, edifice out the wireless dwelling house internet of the futurity is a painstakingly methodical endeavour.

For proof, just look to startups like Starry and Common Networks, which for the past couple years have been building the kind of wireless home net service that the telco giants now want to offer. Both startups are well-funded–Starry raised a $100 million Series C round in July, and Mutual Networks followed with a $25 million Serial B round last calendar month–yet their rollouts are ho-hum-going. Starry hopes to exist in sixteen markets by year-end, nearly three years after launch, and Common Networks is shooting for v total markets by the stop of 2019.

The excruciating footstep could partly be attributed to wireless technology, which is still evolving and could use more spectrum to operate in, merely the bigger factor is more boring: Setting up any kind of cyberspace service in a new urban center–whether it involves cloak-and-dagger cables or airwaves–is just an arduous process.

"At the terminate of the day, this is edifice infrastructure, even though we're building it in this new novel mode, where we don't have to dig up streets and we don't have to get up on poles," says Jessica Shalek, Common Networks' COO. "Like any applied science company that has market-by-market components, that's real work, and that definitely takes some time."

Less cable for less money

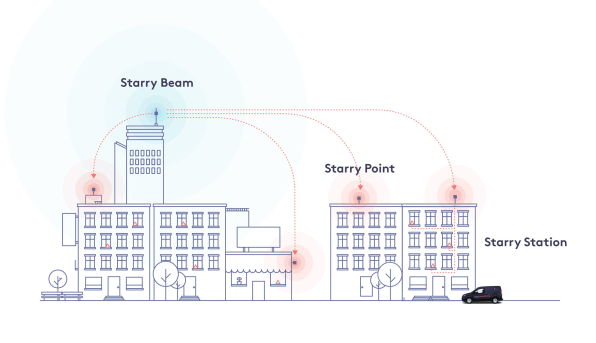

Wireless home internet has been effectually for a couple of decades, mainly in rural communities, but Starry and Common Networks are putting a new spin on the thought for urban and suburban markets. Instead of relying on cellular connections, they set up a network of base stations that communicate through higher-frequency spectrum, similar to what Wi-Fi routers employ. While the range of these base stations is much shorter, the connections are much faster. Common Networks, for instance, offers download and upload speeds of 75 Mbps for $50 per month, and is working on upgrades to 500 Mbps service now.

The base stations then link upwards to larger wired connexion providers, which help feed into the internet backbone. Shalek says most cities and towns have a loftier-speed fiber connection of this nature, only until now, new internet providers oasis't been able to tap into those connections without earthworks upwardly neighborhoods and running cable into everyone's homes at great expense.

Mutual Networks' CEO cofounder, Zach Brock, says getting access to those fiber networks is relatively straightforward. "If you talk to [fiber providers] Zayo, Level three, Cogent, Hurricane Electric, Fastmetrics, even AT&T Enterprise–they're really competitive offerings, and they actually have to work for your patronage, which is dainty. And basically every town, every metropolis, has fiber running downward Main Street."

The wireless arroyo opens the door to new competitors like Starry and Common Networks, who tin can build out service at a fraction of cable's costs. According to the Carmel Group, which conducted a study concluding twelvemonth on behalf of the wireless cyberspace industry, cable is 4.5 times more expensive to build than wireless home net, and fiber is seven times more expensive.

"No one'southward been able to solve how you get that Main Street run downwards to Maple or Oak Street–how do we all go access to that infrastructure? That piece has definitely now been solved," Shalek says.

Why is all this happening now? Brock says it'due south partly due to advances in software-based networking, which allows providers to suit to network conditions on the wing. Simply information technology's also because the cost of high-speed wireless radios, which require massive processing power, has plummeted in contempo years.

"It used to cost thousands of dollars per radio to do gigabit over the air," Brock says. "You lot tin now get fries that are in the dozens of dollars per radio."

Starry and Mutual Networks are hardly alone in building out this kind of service. In Starry's launch market of Boston, some other startup called NetBlazr offers similar wireless service, while PhillyWisper has begun taking on Comcast on its abode turf in Philadelphia.

"At that place are dozens of pocket-size companies around," says Tim Horan, an analyst for Oppenheimer. "There's starting to pop up all over the place."

The approach is also starting to win over telecom giants like Verizon, which has been turning to the same wireless spectrum–chosen "millimeter moving ridge"–for its forthcoming "5G" internet service. Similar Starry and Common Networks, Verizon wants to offer that service as a replacement for dwelling net, arranged with live TV service from providers such as YouTube. (And like those startups, Verizon is also starting tiresome, promising to launch in four markets in October.)

Nevertheless, Claude Aiken, president of the Wireless Internet Service Providers Association (WISPA) trade grouping, believes there's room for smaller companies to compete with larger providers due to the low toll of deployment.

"This is a engineering that has legs," he says.

"On real rooftops, everything that worked in theory breaks downwards"

The biggest question is how long this new breed of dwelling house cyberspace service volition take to get upwards and running.

Common Networks'due south Jessica Shalek says edifice out wireless service is harder and more fourth dimension-consuming than it might seem, in part considering the company has to brand lots of software adjustments along the way. Providing reliable wireless service that accounts for things similar weather, she says, is a hard distributed systems and networking problem to solve.

"Everything works in theory in the networking earth, and it's not like that when you're in the real globe," she says. "When in you're in existent customer homes and on existent rooftops, everything that worked in theory breaks down."

Oppenheimer'due south Tim Horan likewise notes that in that location's a lot of mundane work that goes into installing the base stations, even if they don't involve digging through streets.

"You've got to negotiate with all the edifice owners, you've got to get backhaul, yous've got to become sites on rooftops, and and then you've got to get repeater sites," he says. "And they're wiring each edifice individually, so there'south only so much manpower to exercise that."

At the aforementioned time, companies like Starry and Common Networks accept to be conscientious non to expand across their means, specially when the promise of cheaper, better equipment is always effectually the corner.

"Y'all've got to time information technology where you're getting revenues to support all that capex spending," Horan says. "Yous just can't go out and spend $20 million and not get any revenues on it."

Infrastructure isn't the merely issue. Wireless providers and trade groups similar WISPA are also pushing the Federal Communications Commission to open up up more spectrum, which will allow them to offer better service in more places. They're as well awaiting future technology improvements such every bit the 802.11ax wireless standard, which will allow for even faster speeds between base stations.

But beyond multiple interviews, a simpler reality set in: Physically building these networks is an unavoidably long procedure.

"It's people, information technology's hiring, and putting a team together, and edifice the actual physical deployment of the network," says Virginia Lam Abrams, Starry's senior vice president of communications and regime relations. "It takes time to source vertical assets, and it takes time to build them out."

All of this ways it could be at to the lowest degree another 5 years or more until wireless net starts to feel competitive. That means having multiple options for high-speed cyberspace at dwelling house, not being hostage to data caps, and not being beholden to one company's video service when yous'd rather utilize a competitor'due south.

As startups like Mutual Networks and Starry have discovered, the demand for such a matter already exists. All they have to practise is finish building it.

"That'due south one area where we take a huge advantage," Common Networks' Jessica Shalek says. "This isn't a product you lot have to convince people that they want."

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90234124/fast-wireless-alternatives-to-the-big-isps-cant-grow-fast-enough

0 Response to "Cancel Isp and Start Again for Discount"

Post a Comment